History of Easter Island

Historical summary

A thousand years ago, a small group of polynesians paddled the worlds greatest ocean in search of a new land. For generations, their ancestors had expanded eastwards in the vast Pacific Ocean, guided only by the stars. A new piece of land was found. The settlers of this tiny virgin island called their new home Te Pito o te Henua, meaning "The Navel of the World". The name was seen fit as they were thinking that there can be no place more distant than this... and they were right.

Generations passed, and the inhabitants of what was to be known as Rapa Nui, built a civilization of art, capable of carving, raising and transporting hundreds of gigantic monolith statues, using nothing but their own hands and stone. A glyphic writing called roŋo-roŋo was evolved. A culture had risen, full of achievements, intellect, music and legends - against all odds - in an environment where one would least expect it. Children were well taught of their history and of who they are. Up until today, the Rapa Nui people remember their lineage back to the time when King Hotu Matu'a disembarked at the beach of Anakena lifetimes ago.

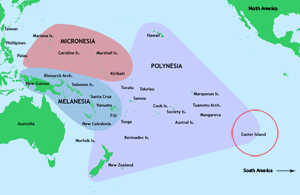

Expansion into Pacific Ocean

1500-2000 BC

Southeast Asian settlers started expanding to the east into the Pacific Ocean. Being extremely isolated and located so far to the east, Rapa Nui was probably the last island to be settled in this expansion. Even today, linguistic traces can still be found in Southeast Asia from the time before the expansion to the Pacific Ocean had started, 4000 years ago.

Settlement

Approx 1000 AD

The settlers reached Easter Island (read more about the first settlers at Easter Island). They found it lush with palm trees and other endemic vegetation growing all over the island. They gave their new home names fitting an island of such isolation, such as Te Pito o te Henua (The Navel of the World) and Mata ki te Raŋi (Eye(s) Looking Towards the Sky).

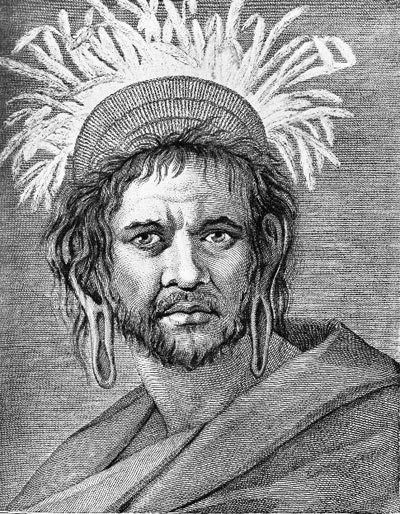

After a while, a second migration of only men arrived to the island. The new inhabitants had a different appearence; they were short and wide. They had a tradition of elongating their earlobes so that they hung down to the shoulders - a tradition that was later practiced also by the first group of settlers. To distinguish the two races they were given names. The first group was called Hanau Momoko - momoko being a duplication of the word moko - lizard - referring to that the people were tall and slender. The second group was called Hanau 'E'epe ('e'epe meaning broad or bulky).

At some point in time, all but one of the Hanau 'E'epe were exterminated by the Hanau Momoko, which means that the Rapa Nui people of today are mainly descendants of the Hanau Momoko.

A civilization grew

Approx. 1200

The early inhabitants of Te Pito o te Henua learnt about the nature of their island and did well in agriculture. The crops were abundant enough for them to invest work into things that didn't produce any food back, and so they developed a tradition of building big rectangular stone platforms called ahu where to bury their kings and important people.

Raising megaliths

Approx. 1400 - 1650

Probably during the 15th or 16th century, the civilization at this small and isolated piece of land was highly advanced. The crops were sufficiently abundant as to support a part of the population to concentrate entirely on building bigger and bigger statues. These megaliths were bought by other tribes and put on the grave platforms (ahu) to commemorate those who had passed away. They called the statues moai - to exist.

Deforestation

Approx. 1650

The islanders grew in numbers throughout the generations. Much of the lush palm tree forests were cut down and burnt to clear areas for crops. During the era of moai building, big quantities of lumber was needed for transportation of the statues. Across generations, more was cut than what sprouted and wood was getting less common. As a result, finished statues awaiting transport started to gather up in the volcanic quarry of Rano Raraku, where virtually all statues were carved. As ultimately the resources of big trees were depleted in the 17th century, the carvers stopped working.

Adapting to new climate

On the contrary to popular belief, the disappearence of the trees did not estinguish the Rapa Nui culture. The islanders adapted well to their tree-less island. The lack of trees made winds dry up the land, but the islanders used different techniques to keep the humidity in the soil. One is the manavai - rings of stone that protected the soil it surrounded to dry out. The less obvious kīkiri was also used - areas covered in stone that would keep the soil below humid. The rain water would also bring minerals from the stones into the earth. Traces of usage of these techniques are highly abundant all over Rapa Nui.

Taŋata manu - birdman competition at Orongo

Approx. 1700 - 1866

From the beginning of the 18th century, when the moai carving period had ended, people started dedicating themselves to some extent to the tangata manu or birdman

competitions in the village of Orongo, situated on the cliffs of volcano Rano Kau. Once the nesting season of the manutara bird (en. sooty tern) started, one representative from each tribe would swim out to the small islet Motu Nui. The first competitor to obtain an egg would swim back and win the title of tangata manu for his chieftain, which would grant great priviledges for both of them as well as the rest of the tribe.

European contact

1722

The first well-documented European contact happened in 1722 with the Dutch admiral Jacob Roggeveen (even if he possibly was not the one to discover Easter Island). He arrived on Easter day, and chose to name the island thereafter. Instantly after disembarking they killed 12 people and injured many more for coming too close. It surely had a great impact on the islanders to see such an advanced technology that the Dutch showed.

Jacob Roggeveen and his crew never reported seeing any statues that had fallen to the ground; every statue they saw was standing. They report that the islanders were well-built, strong and extremely white teeth; strong enough to open nuts with.

With Easter Island being known to the outside world, European visits gradually increase, especially during the 19th century.

Slave raids

1862 - 1863

The visiting Europeans generally estimate the islanders to be in the number of thousands, until the beginning of the 1860's when 1500 islanders were taken to work as slaves, which would mean most able-bodied men. Among the kidnapped were the ruling king as well as the wise men who knew how to read the rongo-rongo script, which today no one is left to interpret.

The slaves worked in guano deposits at Chincha Islands and plantations in Peru. A few of these were later released, all of which died of small-pox on the return voyage, except for two people. These two spread the disease to the rest of the Rapa Nui population. The natives had no immune system towards this foreign disease, which resulted in an aggressive decrease of the population. A few years later, only 111 people were left at the island.

Abandoning the old culture

1866

Catholic missionary Eugenio Eyraud heard about the unfortunate happenings at Rapa Nui, so he went for a nine month visit in 1864. Two years later, he established a Catholic mission. The missionaries told the natives to abandon their old practises, such as that of the birdman competition, which they did. They converted all natives to christianity. No slave trade ever occurred at Easter Island again.

Annexation to Chile

1888

No colonising country had any particular interest in Rapa Nui because of its remoteness. Britain recommended Chile to claim it to keep France from doing it first. In 1888, Chilean naval captain Policarpo Toro let the current Rapa Nui king Atamu Tekena (who wasn't really of straight royal lineage, but only someone assigned by the real king to rule) sign a deed, giving Chile full and entire sovereignty

over the island, while the Rapa Nui translation used words such as friendship

and protection

. Even so, 1888 is officially the year when Rapa Nui became Chilean.

The treaty also consisted of a symbolic act; Atamu Tekena took grass in one hand and dirt in the other. He gave Policarpo Toro the grass and kept the dirt for himself, meaning that the Rapa Nui people always will be true owners of their own land. Among Rapa Nui people, Chileans are still today sometimes referred to as mauku - grass

.

Williamson Balfour & Co.

1903 - 1953

Rapa Nui was left alone by Chile until 1903, when the British/Chilean company Williamson Balfour & Co. set up Easter Island Exploitation Company and signed a contract to lease thei sland as a sheep farm for 50 years. The natives were fenced in around guarded borders in the area that today is the town of Hanga Roa to prevent sheep theft. Up to 70 000 sheep roamed the island freely. After 1936, conditions were improved. Natives were able to visit the countryside if a permission in written form had been asked and granted. Each family was also given a sheep every now and then. After the Second World War, syntetic wool was invented, which complicated the market for Easter Island Exploitation Company. As a result of this, together with the constant native uprisings, the company did not renew the contract, but left the island in 1953.

Rapa Nui today

The Rapa Nui people are today around 3000, though not many of the new-born have two Rapa Nui parents. The native language is not widely spoken; mostly among elders. People born in the 1980's or later are often only able to hold simple conversation in Rapa Nui, and tend to change into Spanish quite quickly. Deeper knowledge of the ancient Rapa Nui language is today somewhat of an exclusivity.

Chile today takes well care of the Rapa Nui culture and the government does what it can to help the islanders to do the same. Through an institution called CONADI they offer to pay the costs of well-planned projects presented by the islanders that intend to help with the preservation of the culture in any way. One might see it as some kind of conciliation of the unfortunate events that the world has brought upon the small island of Rapa Nui.

Read more about modern Easter Island society.

Rongo-rongo - the lost Rapa Nui writing language

Rongo-rongo (roŋo-roŋo in Rapa Nui) is an ancient Easter Island glyph writing. It is the only known native writing in all of Polynesia. Rongo-rongo uses symbols of items, as with the Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The rongo-rongo symbols were written on tablets of wood. Today, only around 25 rongo-rongo tablets are known to exist; all scattered at museums outside of Easter Island.

Lost knowledge

In 1862-1863, many slave raiders attacked Rapa Nui. All able-bodied men were taken, among them all the wise men who knew how to read and write rongo-rongo. Since then, no one knows how to interpret the tablets. Several linguists have tried, but there is no generally accepted theory of how to read the symbols.